- The rise of the Arab Caliphate

- Astronomy in the Arab Caliphate

- Advancements in Arab astronomy

- Astronomy in Central Asia

- Al-Biruni: The First Encyclopedic Scholar of the Arab World

- The Maragheh observatory and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

- Ulugh Beg: The greatest astronomer of the 15th Century

- The development of Ptolemaic astronomy

- Forgotten ideas: Omar Khayyam and the infinity of the Universe

- The Legacy of Medieval astronomy

The rise of the Arab Caliphate

A powerful state—the Arab Caliphate—was formed in the 8th–10th centuries as a result of the conquest wars waged by Arab tribes from the Arabian Peninsula, united under the banner of a new religion—Islam. This vast empire stretched from present-day Iran, Iraq, and Central Asia in the east to North Africa and Spain in the west.

However, the conquerors themselves became “captives” in a different sense—they were captivated by the superior culture of the peoples they had subdued. Arab civilization flourished by absorbing the cultural heritage of the Byzantine colonies, which had preserved the achievements of ancient Greek science. The growth of Arab culture continued even after the Caliphate fragmented into separate states by the 10th century.

Astronomy in the Arab Caliphate

Although Arab scholars gained access to the treasures of ancient science and culture as early as the 7th century, they only began systematically studying them a century later, primarily through Indian sources. One of the early Abbasid caliphs, Al-Mansur (known in Europe as Almanzor), gathered scholars from the West and India.

By his order, during the last quarter of the 8th century, the Indian Siddhantas of Aryabhata and Brahmagupta were translated into Arabic. The first attempts to fully translate Ptolemy’s famous Megale Syntaxis (later known as The Almagest) were made in the same century by two Jewish scholars under the directive of the new caliph, Harun al-Rashid. However, these early translations were unsuccessful.

During the reign of his son, Al-Ma’mun, an academy of sciences—the House of Wisdom—was established in Baghdad, along with an astronomical observatory. At the House of Wisdom, a group of scholars, led by a Syrian scientist, undertook the direct translation of scientific texts from Ancient Greek. The first complete translation of Ptolemy’s great work was successfully completed in the 9th century by the Arab scholar Thabit ibn Qurra (836–901).

Advancements in Arab astronomy

Exposure to the Indian adaptation of Ptolemy’s theories, and even more so the translation of The Almagest, stimulated the development of observational astronomy in the Arab world. This also led to advancements in the necessary mathematical tools for astronomy.

One notable astronomer, Al-Battani (known in Europe as Albatenius), who lived in the Syrian city of Raqqa between 878 and 918, refined the calculation of the inclination of the ecliptic relative to the equator.

Another prominent scholar, Abu al-Wafa (940–997/998), discovered a new irregularity in the Moon’s motion—later known as the variation—which describes changes in the Moon’s velocity.

By the end of the 10th century, new scientific centers of Arabic culture were established in various places at different times: Cairo, where, again at the court of the ruler, the House of Knowledge and an observatory were founded, in which the famous astronomer Ibn Yunus (950-1009) worked; Isfahan, where the largest observatory of the time was located, and where the famous poet and scholar—mathematician and astronomer Omar Khayyam (1048—after 1122) worked.

Having learned from Greek books how to make astronomical angular measuring instruments—sextants and quadrants—the Arabs significantly improved the precision of measurements with them, increasing their size and transitioning to long-term systematic observations. The invention of a new universal astronomical-geodetic instrument—the astrolabe—belongs to the Arabs themselves. Soon, they noticed the inaccuracy of Ptolemy’s astronomical tables. Therefore, their main efforts were directed at compiling new solar, lunar, and planetary tables, as well as star catalogs.

These works, called zij, were produced in large numbers throughout the entire period of the existence of Arab astronomy. Such an observational direction of medieval astronomy in the Middle East continued in the new scientific centers that emerged in the Middle East.

Astronomy in Central Asia

Between the 10th and 15th centuries, three new astronomical centers emerged, territorially belonging to Central Asia (partially in present-day Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan) but also culturally and linguistically tied to the Arab world.

One of the earliest of these centers was the city of Ghazni, located in the southeast of modern Afghanistan, just over 100 km southwest of Kabul. At the time, Ghazni was the capital of the powerful Ghaznavid state, ruled by the Mongol conqueror Mahmud of Ghazni.

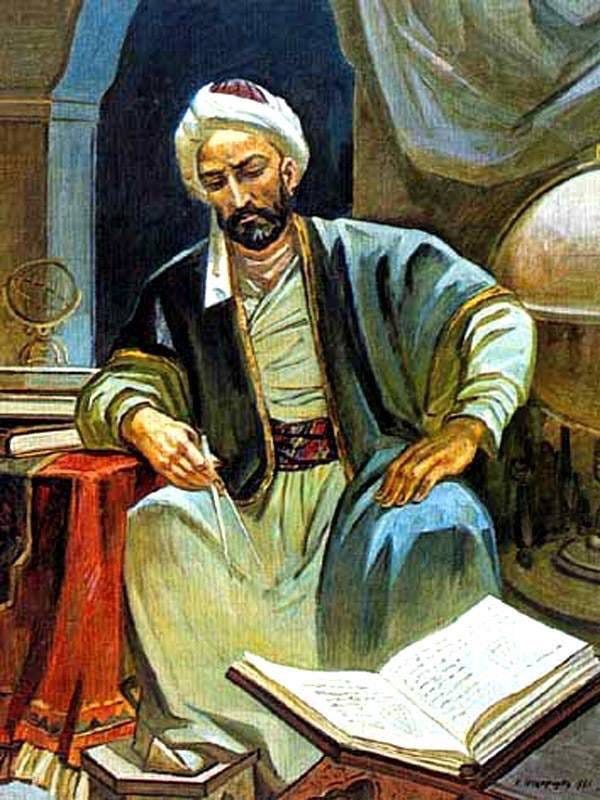

Al-Biruni: The First Encyclopedic Scholar of the Arab World

For a long period, the great Central Asian scientist and philosopher Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973—c. 1050) lived and worked at Mahmud’s court. Al-Biruni was originally from the region (biruni in Arabic) of the city of Kyat, the capital of ancient Khwarezm.

Al-Biruni was the first encyclopedic scholar in the Arab world. His extensive body of work—over 150 books—covered fields such as:

- Astronomy and Geography

- Physics and Mathematics

- Geology and Mineralogy

- Chemistry and Botany

Despite these sciences being in their early stages, Al-Biruni contributed significantly to their development. He was also an outstanding historian and ethnographer, documenting the cultural and scientific history of various regions. His major work, India (1030), was a groundbreaking study of Indian culture, written after he spent several years in the country as a court scholar-prisoner during Mahmud of Ghazni’s military campaigns.

More than 40 of Al-Biruni’s works were dedicated specifically to mathematics and astronomy.

Al-Biruni’s contributions to astronomy

Al-Biruni was an exceptional observer and instrument maker. His key contributions included:

- Constructing a massive stationary wall quadrant with a 4-meter radius, which enabled the precise measurement of the Sun and planets’ positions with an accuracy of 2’—an achievement that remained unsurpassed for three centuries.

- Improving the astrolabe, making it a more effective tool for celestial observations.

- Creating the first geographical globe (or half-globe) with a diameter of 5 meters. This device allowed for the rapid determination of one location’s coordinates based on known reference points.

Unfortunately, none of Al-Biruni’s astronomical instruments have survived to the present day.

The works and discoveries

Fundamental writings

Al-Biruni presented his numerous and diverse studies and results in several fundamental works, including:

- The Book of Interpretation of the Fundamental Principles of Astronomy

- The Canon of Mas’ud (astronomical tables and a star catalog, traditionally dedicated to the ruler Mas’ud, son of Mahmud of Ghazni)

- Geodesy

- Mineralogy

The first two works served as the main astronomy textbooks in the Arab world and the East for several centuries.

Astronomical measurements and discoveries

Al-Biruni measured the tilt of the ecliptic relative to the equator with remarkable accuracy (23° 50′ 34″) and discovered its variability over time. He estimated the maximum distance to the Moon as 64 Earth radii (modern value: 63.5), measured a degree of the meridian, and calculated the Earth’s radius by observing the dip of the horizon from a mountain peak. His calculations, when converted to European units, yielded values of 110.278–110.691 km per degree of meridian and 6403 km for Earth’s radius—remarkably close to modern data for that latitude.

The star catalog in The Canon of Mas’ud

The ninth of the eleven books in The Canon of Mas’ud is almost entirely dedicated to an extensive catalog of 1,029 stars, whose positions Al-Biruni recalculated from earlier Arab zij tables, accounting for precession. The precession constant he used—52.46″ per year—was refined by Ulugh Beg only four centuries later.

Translations and critique of Ptolemy

Al-Biruni was the first to fully translate Ptolemy’s Almagest and Euclid’s Elements into Sanskrit for Indian scholars. He also critically analyzed Ptolemaic cosmology, offering his own insights.

Views on celestial bodies

Al-Biruni considered the Sun and stars to be fiery spheres, while the Moon and planets were dark bodies that reflected sunlight. He suggested that stars were hundreds of times larger than Earth, echoing the real measurements of the Sun, such as those made by Aristarchus of Samos. He believed stars were similar to the Sun, capable of movement, and explained their apparent immobility by their immense distance.

In The Canon, he was likely the first to mention the existence of “double stars,” which appear as single points of light only due to the limitations of human vision. He was also among the first since the ancient Greeks to consider the nature of the Milky Way, proposing that it was a vast collection of stars.

Early observations of zodiacal light and meteorites

Al-Biruni may have been the first to describe the faint glow of the sky before dawn and after twilight, likening it to a “wolf’s tail”—now known as zodiacal light. In his Mineralogy, he recorded the first known description in astronomical history of a meteorite rain, which fell in Bushanj (India).

Refusal of the Sultan’s reward

A well-known account states that the ruler of Ghazni ordered Al-Biruni to be rewarded with an elephant’s tusk filled with silver for his work The Canon of Mas’ud. However, Al-Biruni declined the gift, saying:

“This gift will distract me from my scientific work. Wise people know that silver fades away, but knowledge remains.”

Al-Biruni’s recognition in Europe

Al-Biruni became known in Europe only in the 19th century, following the publication of the English translation of his work India in 1888.

The Maragheh observatory and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

By the mid-13th century, the city of Maragheh (located in present-day Iranian Azerbaijan) became a major center for astronomy in Central Asia. In 1259, a special observatory was built there, employing around one hundred scholars. The leading figure at this institution was the outstanding Central Asian astronomer, mathematician, poet, and philosopher, Muhammad ibn Hasan Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1201–1274), a native of Hamadan (Azerbaijan).

In 1256, Hulagu Khan, the grandson of the famous Mongol conqueror Genghis Khan, captured Azerbaijan and Persia (modern-day Iran). He freed Nasir al-Din from the fortress of Alamut (also known as the “Eagle’s Nest”), where the scholar had been imprisoned for over 20 years by a secret religious-political terrorist organization during his travels.

Recognizing Nasir al-Din’s reputation, Hulagu Khan appointed him as a court scientist and advisor on state affairs. Following the final victory over the Arab Caliphate, the khan, influenced by Nasir al-Din, relocated the capital of his new state to Maragheh, the ancient capital of Azerbaijan.

Instruments and achievements of the Maragheh observatory

Among the many remarkable instruments at the Maragheh Observatory, the most notable was a wall quadrant with an arc radius of 6.5 meters. Nasir al-Din significantly refined the precession constant, determining it to be 51.4″ per year (modern value: 50.2″).

After 12 years of work, in 1271, the observatory produced a new zij—the Ilkhanic Tables (named after the Ilkhans, the successors of Hulagu Khan). In addition to lunar, solar, and planetary tables, this work included a new star catalog. For two centuries, these tables served as the basis for annual calendar calculations across the Middle East.

Contributions to mathematics and philosophy

Nasir al-Din was also an outstanding mathematician. His Treatise on the Complete Quadrilateral played a crucial role in the formalization of both plane and spherical trigonometry as independent scientific disciplines.

Beyond astronomy and mathematics, he was a renowned Persian thinker. He is recognized worldwide as the legendary Hodja Nasreddin, whose name is associated with countless humorous stories and anecdotes.

Ulugh Beg: The greatest astronomer of the 15th Century

Perhaps the most famous medieval astronomer of Central Asia was Ulugh Beg (1394–1449), the grandson of the formidable Tamerlane.

Medieval astronomers of the Near and Middle East earned renown as skilled observers of the starry sky and builders of some of the world’s first large observatories and instruments. However, their research centers often fell into ruin shortly after their deaths—due to the vast gap between the intellectual level of a small group of scholars and the overall culture of the majority of the population in these empires.

The development of Ptolemaic astronomy

Regarding Ptolemy’s theory itself, Arab and later Central Asian astronomers primarily worked on refining its mathematical framework. The principle of geocentrism was not questioned.

Arab scientists did not introduce fundamentally new ideas into the general worldview. The one notable exception was the great thinker Al-Biruni. However, even his insights into the structure of the universe were not firmly established and remained unknown to European science until the late 19th century.

Forgotten ideas: Omar Khayyam and the infinity of the Universe

Even more ahead of their time were the statements of Omar Khayyam regarding the infinity of the universe. These ideas found no resonance in his era, were completely forgotten in the East, and reached the West only in the mid-19th century.

The Legacy of Medieval astronomy

The primary legacy of medieval astronomers from the Near and Middle East was their numerous zij (astronomical tables), of which around a hundred have been preserved. These works continued to be valuable resources for the study of the stars in the following centuries.

Sources we used to write this article:

- Astronomy. Encyclopedia for children. 1997. ISBN 5-89501-008-3

- https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/astronomy-and-astrology-in-the-medieval-islamic-world

- https://early-astronomy.classics.lsa.umich.edu/islamic_intro.php

- https://indico.icranet.org/event/2/contributions/1108/attachments/343/507/Isfahan_Kerner2021B-3.pdf

- https://www.newarab.com/features/staring-heavens-astronomy-medieval-islam

- https://aboutislam.net/science/science-tech/islamic-golden-eras-astronomers/

- https://www.britannica.com/science/astronomy/India-the-Islamic-world-medieval-Europe-and-China

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astronomy_in_the_medieval_Islamic_world

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_scientists_in_medieval_Islamic_world

- https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36268

- https://www.routledge.com/Reflections-on-Observational-Astronomy-in-the-Medieval-Islamic-Period/Mozaffari/p/book/9781032772349

Leave a Reply